BEIJING DOOMED. HIGH-ENERGY COLLISION CAN RESOLVE THE GREAT TIBET PROBLEM

The Great Tibet Problem is described as illegal, illegitimate, military occupation of Tibetan Territory by a foreign invading force. The Great Tibet can be resolved by the application of physical force of a great magnitude that can evict the Occupier of Tibet without any further human intervention or effort.

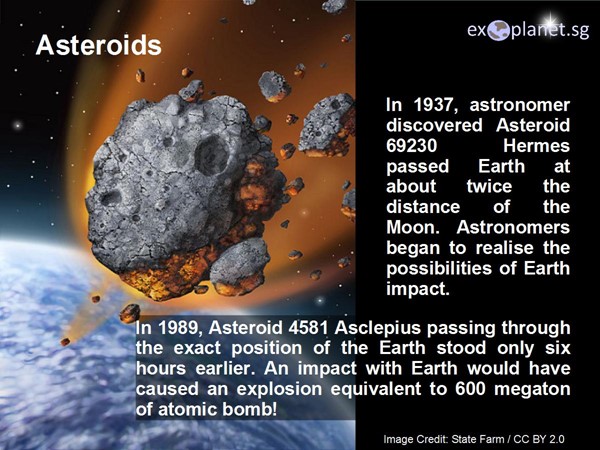

Such forces with devastating power do exist in Nature. Planet Earth experienced the serious consequences of heavenly bodies such as asteroids, bolides, and meteorites colliding with Earth. These heavenly bodies acquire massive amounts of energy as Earth’s Force of Gravitation accelerates them as they enter Earth’s atmosphere.

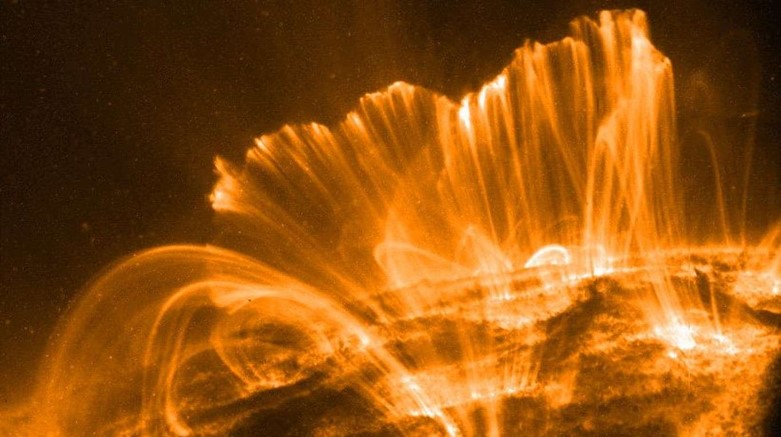

The discovery of the highest-energy gamma rays by the Tibet ASgamma Experiment gives the hope of a Heavenly Strike acting to neutralize the military power of Tibet’s Occupier. While the gamma rays are prevented by Earth’s atmospheric shield from causing damage, the impacts by Near Earth Objects will not be undermined by the natural protection afforded by the Magnetosphere.

Rudranarasimham Rebbapragada

Special Frontier Force

The highest-energy gamma rays discovered by the Tibet ASgamma experiment

Clipped from: https://phys.org/news/2019-07-highest-energy-gamma-rays-tibet-asgamma.html

The left figure shows the Tibet ASgamma experiment observed the highest energy gamma rays beyond 100 Teraelectron volts (TeV)from the Crab Nebula with low background noise, the cross mark indicates the Crab pulsar position. And the right figure shows the Crab Nebula taken by the Hubble Telescope Credit: NASA

The Tibet ASgamma experiment, a China-Japan joint research project, has discovered the highest energy cosmic gamma rays ever observed from an astrophysical source—in this case, the Crab Nebula. The experiment detected gamma rays ranging from > 100 Teraelectron volts (TeV) (Fig.1) to an estimated 450 TeV. Previously, the highest gamma-ray energy ever observed was 75 TeV by the HEGRA Cherenkov telescope.

Researchers believe the most energetic of the gamma rays observed by the Tibet ASgamma experiment were produced by interaction between high-energy electrons and cosmic microwave background radiation, remnant radiation from the Big Bang.

The Crab Nebula is a famous supernova remnant in the constellation Taurus. It was first observed as a very bright supernova explosion in1054 AD (see Fig.1). It was noted in official histories of the Song dynasty in ancient China as well as in Meigetsuki, written by the 12th century Japanese poet Fujiwara no Teika. In the modern era, the Crab Nebula has been observed using various types of electromagnetic waves including radio and optical waves, X-rays and gamma rays.

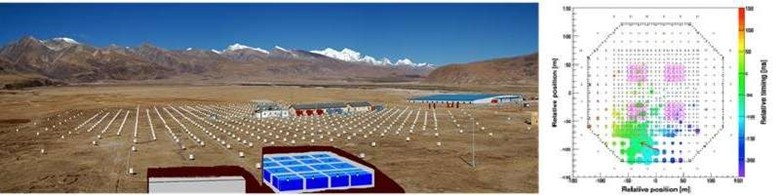

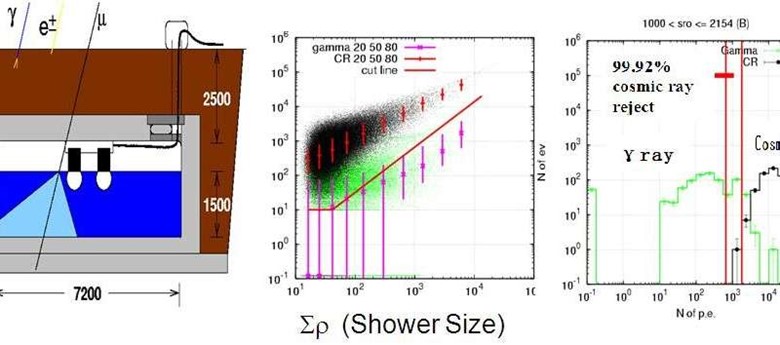

The Tibet ASgamma experiment has been operating since 1990 in Tibet, China, at an altitude of 4300 meters above sea level. The China-Japan collaboration added new water Cherenkov-type muon detectors under the existing cosmic-ray detectors in 2014 (see Fig.2). These underground muon detectors suppress 99.92 percent of cosmic-ray background noise (see Fig.3). As a result, 24 gamma-ray candidates above 100 TeV have been detected from the Crab Nebula with low background noise. The highest energy is estimated at 450 TeV (see Fig.2).

The left figure shows the Tibet ASgamma experiment (Tibet-III array+ Muon Detector array); The right figure shows an event display of the observed 449TeV photon-like air shower. Credit: IHEP

The researchers hypothesize the following steps for generating very-high-energy gamma rays: (1) In the nebula, electrons are accelerated up to PeV, i.e., peta (one thousand trillion) electron volts within a few hundred years after the supernova; (2) PeV electrons interact with the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR) filling the whole universe; (3) A CMBR photon is kicked up to 450 TeV by the PeV electrons. The researchers thus conclude that the Crab Nebula is now the most powerful natural electron accelerator discovered so far in our galaxy.

This pioneering work opens a new high-energy window for exploring the extreme universe. The detection of gamma rays above 100 TeV is a key to understanding the origin of very-high-energy cosmic rays, which has been a mystery since the discovery of cosmic rays in 1912. With further observations using this new window, we expect to identify the origin of cosmic rays in our galaxy, namely, pevatrons, which accelerate cosmic rays up to PeV energies.

The China-Japan collaboration placed new water Cherenkov-type muon detectors under the existing cosmic-ray air-shower array in 2014. These underground muon detectors can suppress 99.92% of cosmic-ray background noise. Credit: IHEP

“This is a great first step forward,” said Prof. HUANG Jing, co-spokesperson for the Tibet ASgamma experiment. “It proves that our techniques worked well, and gamma rays with energies up to a few hundred TeV really exist. Our goal is to identify a lot of pevatrons, which have not yet been discovered and are supposed to produce the highest-energy cosmic rays in our galaxy.”