Whoops! Tibetans Win Freedom Playing Hoops

Whoops! It’s Hoop Time in Tibet. It gives me Whole Hope. I am hoping that Tibetans will begin scoring Wins on the playground which will ultimately lead to a Win on the battlefield. I am praying for the time to announce Tibetan Victory in the Hoops Game. As the saying goes, “The Battle of Waterloo was Won on the Playing Fields of Eton.” The saying emphasizes that the foundations for victory at Waterloo, and by extension, British military prowess, were laid through the discipline, teamwork, and leadership skills developed during a public school education. The quote suggests that the values of courage, discipline, and teamwork, which are crucial in war, were instilled in British officers during their time at prestigious public schools like Eton. Freedom does not come automatically even if you live at the ‘Rooftop’ of the World. Tibetans need to ascend to a new level where they can outplay their opponents in a Game of Strength and Will Power.

Rudra Narasimham Rebbapragada

Special Frontier Force-Establishment 22-Vikas Regiment

Basketball in Tibet: A Sport’s Unlikely Ascent

Clipped from: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/01/tibet-basketball/576421/

Monks, nomads, and a sport’s unlikely ascent in a remote corner of the globe

An Rong Xu

ALONG the northeastern edge of the Tibetan plateau, a treacherous landscape where yaks graze above the clouds, basketball hoops are everywhere: at the bases of cliffs; in the courtyards of centuries-old, golden-roofed monasteries; in nomadic villages tucked into the hills.

It was within such a village, Zorge Ritoma, that Dugya Bum, a sheep and yak herder from the Golden Stone Clan, took up the sport. He’d played in school, but after dropping out at 16 he became a full-time nomad, the livelihood of his ancestors. During winter, his family lived in a mud-walled house about four miles from Zorge Ritoma’s center, grazing yaks and sheep at the foot of the mountains. In the summer, when the weather improved, they took the herds up to rich, high-altitude pastures and resided in temporary tents. In the fall, they would gradually make the journey back down.

As a teenager, Dugya Bum grew his hair long and smoked cigarettes. He avoided eye contact. His parents, all too familiar with the physical demands of a permanent nomadic existence, encouraged him to explore alternative life paths. So in 2011, he took a job at Norlha, a textile company that had opened in the village a few years earlier and was hiring nomads as yak-wool artisans. But the routines of office and factory work didn’t suit him.

Then, in 2015, a tall, gangly stranger arrived from the United States. The newcomer set about putting together a real basketball team, with practices and drills and tournaments and all the rest. Dugya Bum signed on to play after work. The sport became central to his life. The team generated excitement throughout the village, and in the nomadic communities beyond. Now, going on four years later, a semi-professional sports program is flourishing and spreading hope, in a region better known for its reincarnated lamas than its athletes.

A few years ago, while living in Queens, I began to wonder whether any Buddhist monks played hoops. I’d loved the sport since childhood and had recently become fascinated by practitioners of Buddhism. And while the pairing may seem far-fetched, it made a certain sense to me. Devotion to the sport involves countless hours in the solitude of echoing, dimly lit places—rickety old gymnasiums, empty playgrounds, driveways late at night—where one undergoes a genuinely meditative sensory experience: the rhythmic bouncing of a ball; the mental focus and repetition essential for knocking down free throws; the visualizations, such as imagining oneself sinking a last-second shot. There’s a reason Phil Jackson—a.k.a. the Zen Master—didn’t coach football.

I visited a few Buddhist monasteries in the New York area, where I was met with a consistent response from the polite but puzzled residents: No, monks don’t play basketball. That seemed to be that.

But there’s always the internet. Late one evening in 2017, I Googled basketball and Buddhist monk and eventually found a Facebook page on which a grainy video had been posted. It showed a red-robed monk on an outdoor court effortlessly leaping up, grabbing the rim, and shattering the backboard. I initially suspected this was a hoax, but if so, it was an elaborate one. In one picture on the page, a man stood on a mountaintop amid rising smoke. “Team captain Jampa making offerings and passionate prayers to his village’s mountain gods before a basketball match,” the caption said. In another picture, a flock of sheep approached a basketball court beside a barren hill. “And the fans rush the court!” that caption said. I saw a picture of young nomadic women shooting baskets on a snowy, icy court, and a video of a young monk executing a pretty up-and-under move to evade a shot-blocker and put the ball in the hoop. This, it turned out, was Norlha basketball.

A red-robed monk effortlessly leaped up and shattered the backboard.

I contacted Willard “Bill” Johnson, the team coach and the moderator of the Facebook page. He told me, in a dreamy voice, that the people of Tibet were mad for hoops.

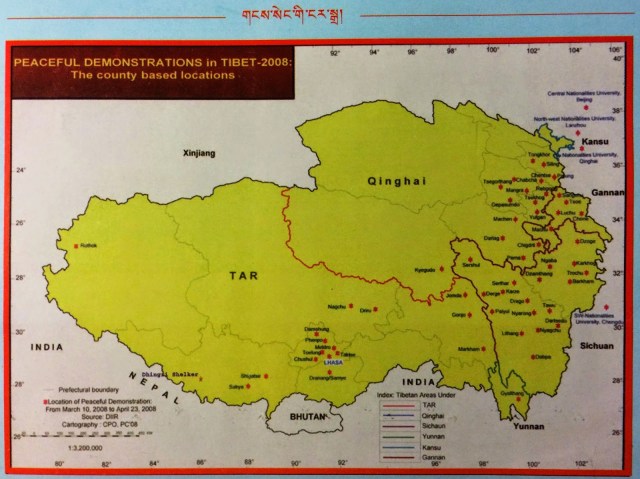

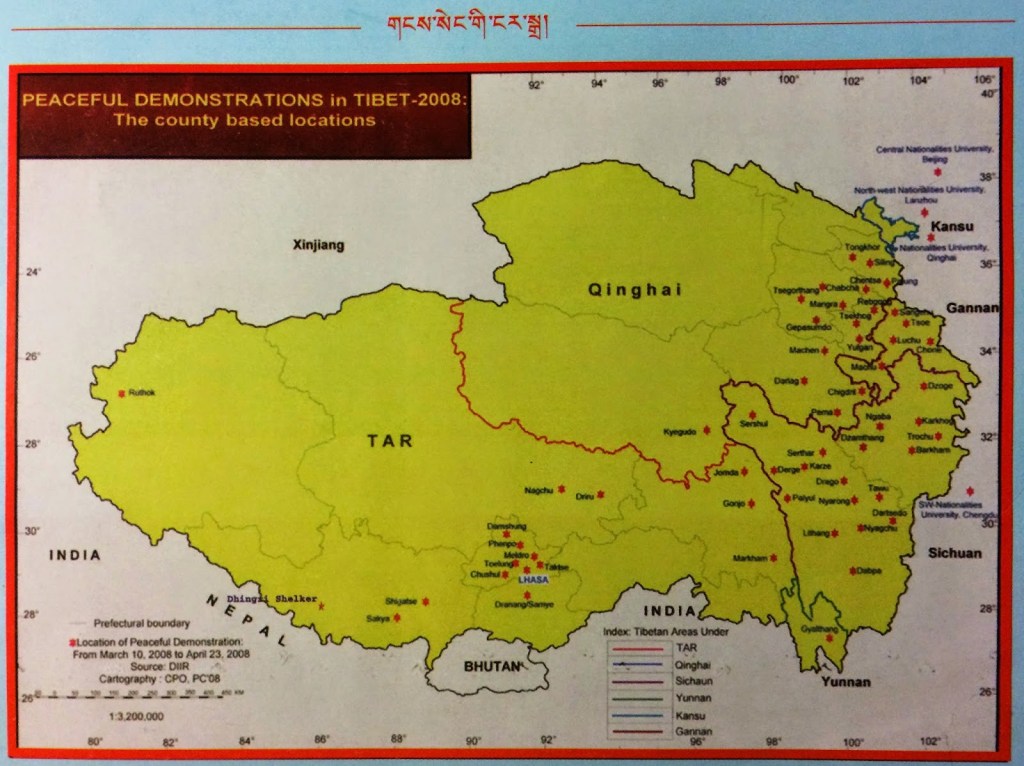

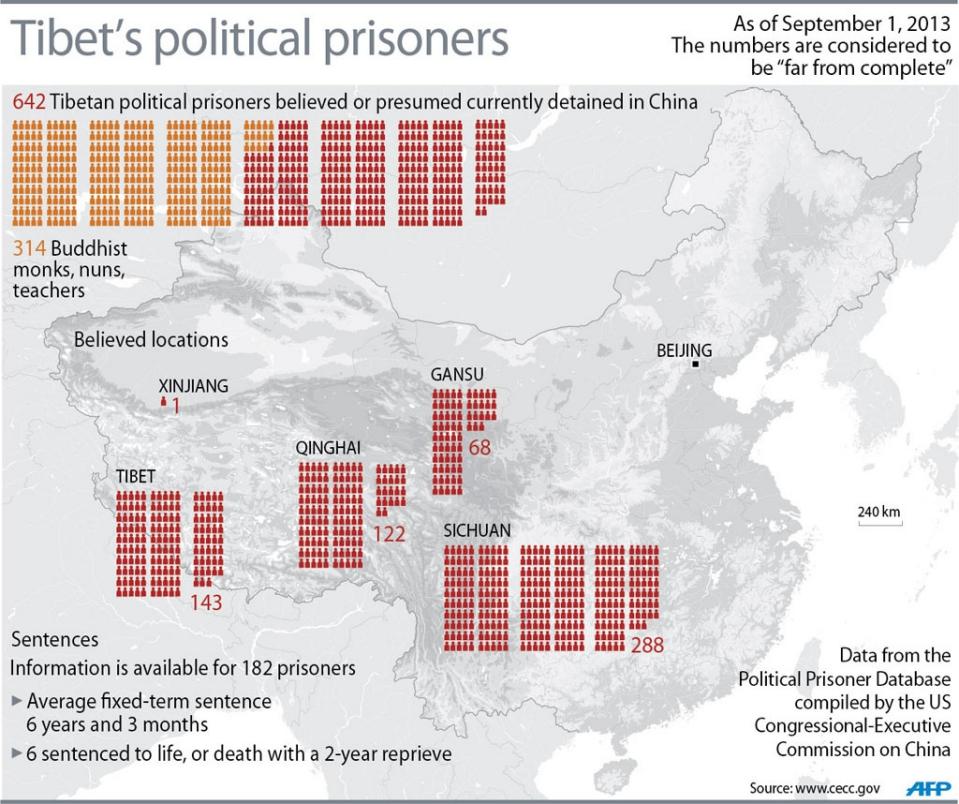

Johnson described to me the upcoming Norlha Basketball Invitational and Tibetan Hoop Exchange, featuring a tournament that he said would showcase the top teams—some composed of nomads, others of monks—in the Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. (Gannan is part of China’s Gansu province and is located in the traditional Tibetan region of Amdo.) Johnson called it a “turning point” for his team— “our big test.” The tournament would gauge his players’ strength against tougher competition than they had yet seen. Excited, I made travel arrangements to attend the tournament. The next day, alas, it was postponed. The tournament would have coincided with the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in Beijing, for which security was being tightened throughout the country. Local police from China’s Public Security Bureau, concerned about large gatherings, had asked Norlha for the postponement.

I decided to make the journey, nonetheless.

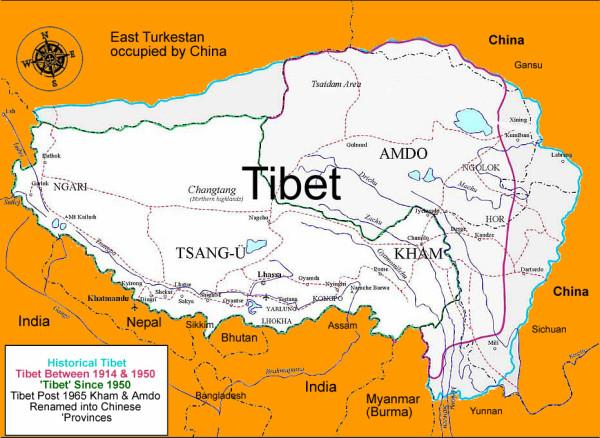

Basketball first appeared in the Tibetan highlands about 100 years ago. At that time, the rugged, sparsely populated Tibetan plateau was ruled by warlords on its eastern frontier and in central and western Tibet by the Buddhist government of the Dalai Lama.

According to Chinese historical records, in 1935 central Tibet sent a basketball team to the Sixth National Games in Shanghai, more than 2,500 miles from the Tibetan capital of Lhasa. But the team didn’t arrive until after the tournament was over. An overland trip would have taken several months on horseback, Tibet historians told me, with provisions carried by yaks or mules.

Sheep being herded in Zorge Ritoma. (An Rong Xu)

In his book Seven Years in Tibet, the Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer wrote that upon his arrival in Lhasa in 1946, the city “made no provision for games,” with one exception: “a small ground for basketball.” Particularly in eastern Tibet, the sport spread in part for topographic reasons: The uneven and rocky landscape encouraged basketball over soccer, which requires a much more level ground.

In 1951, China’s People’s Liberation Army, including a military basketball team, marched into central Tibet and occupied—or “peacefully liberated,” in the Chinese view—the region. It would be another eight years before the Dalai Lama fled from Lhasa into exile in India. During the interim, championship basketball games were held in a large open space in front of the Potala Palace, the Dalai Lama’s enormous hillside residence. Dongak Tenzing, 83, a former Tibetan soldier who grew up in Lhasa and now lives in Madison, Wisconsin, described them to me. Thousands of people would attend, Tibetan townspeople, government and palace officials, uniformed Chinese military personnel, aristocrats, and monks. Food and drink stalls surrounded the manicured dirt court, and the score was displayed on a blackboard. The games—which were organized by the Chinese—were clean and disciplined, Dongak remembered. Rough play was prohibited, as were displays of emotion, which were considered rude.

Nomads have lived in the Zorge Ritoma area since at least the 17th century. Until the late 1950s, they lived in yak-wool tents year-round; by the 1960s, when they started building dwellings with mud walls to stay in during the winter, basketball was an important part of village life for young men, according to Dugya Bum’s grandfather Gonpo Tashi, who played as a child. The basketballs used at that time, he said, were made from the bladders and skin of freshly slaughtered animals; while lacking the bounce necessary for proper dribbling, they were adequate for passing and shooting.

In Zorge Ritoma, villagers played a rough, unusual variation of basketball using a wooden hoop, Jampa Dhundup, a point guard and leader for Norlha’s team, told me. According to the rules, the ball couldn’t touch players below the waist. And “whichever team fought the best won—no one thought about skill.”

In the late 1990s, television started trickling into remote areas. At the same time, basketball was becoming a favorite pastime of Tibetan monks. Johnson mentioned to me an old tradition of “big, strong monks who were athletes”—an apparent reference to the dobdobs, the physically aggressive monks who carried weapons, engaged in sporting competitions, and served as monastic police and bodyguards for important lamas and other travelers.

Alex McKay, a Tibetologist and sports historian of the Himalayan region, suggested to me that the macho image of the American basketball star likely appeals to eastern Tibetans because they have roots in a warrior culture. As one Tibetan player from Amdo told Chinese media during a tournament in March: “We don’t have professional coaches back home. All of us learned to play by watching NBA and CBA games on TV, by following the players’ movements. No one gave us any direction.”

Zorge Ritoma, known among locals simply as Ritoma, sits at the base of four sacred peaks. Its 275 families are scattered across several valleys in red- and pink-roofed houses, now mostly made of brick or stone. Much of the village’s food is derived from yaks—meat, cheese, butter, and yogurt—and religion is embedded in everyday life. “Sky burials,” in which the body is taken to a mountaintop and prepared for vultures, are performed on the dead.

In 2007, Kim Yeshi—a French American who studied anthropology and Tibetan Buddhism in college and married a Tibetan man in 1979—along with her daughter, Dechen Yeshi, co-founded the Norlha plant in Ritoma. The intent was both to preserve Tibetan culture and to offer a consistent source of income to the villagers. A year later, Kim decided to have a basketball court built to accommodate the community’s obsession with the game. It’s a paved surface adjacent to a workshop on a narrow, relatively flat stretch between Ritoma’s main road and a hill whose incline doubles as makeshift bleachers.

The employees played after work. Using one or two basketballs, they congregated around the hoop and heaved up shots. A regular at the court was Dugya Bum. As the eldest son, he would normally have been expected to carry on as the nomadic heir to the family’s herds and have a wife chosen for him. Instead, shortly after he dropped out of school, his grandfather approached Norlha’s executives and asked, “Do you have something he can do?” Norlha trained Dugya Bum to use an office computer, speak rudimentary English, and take photographs of models wearing the scarves the company manufactures from yak wool. He liked the photography, but didn’t excel at it; principally, he saw it as an opportunity to get closer to a particular model, Lhamo Tso, with whom he had fallen in love.

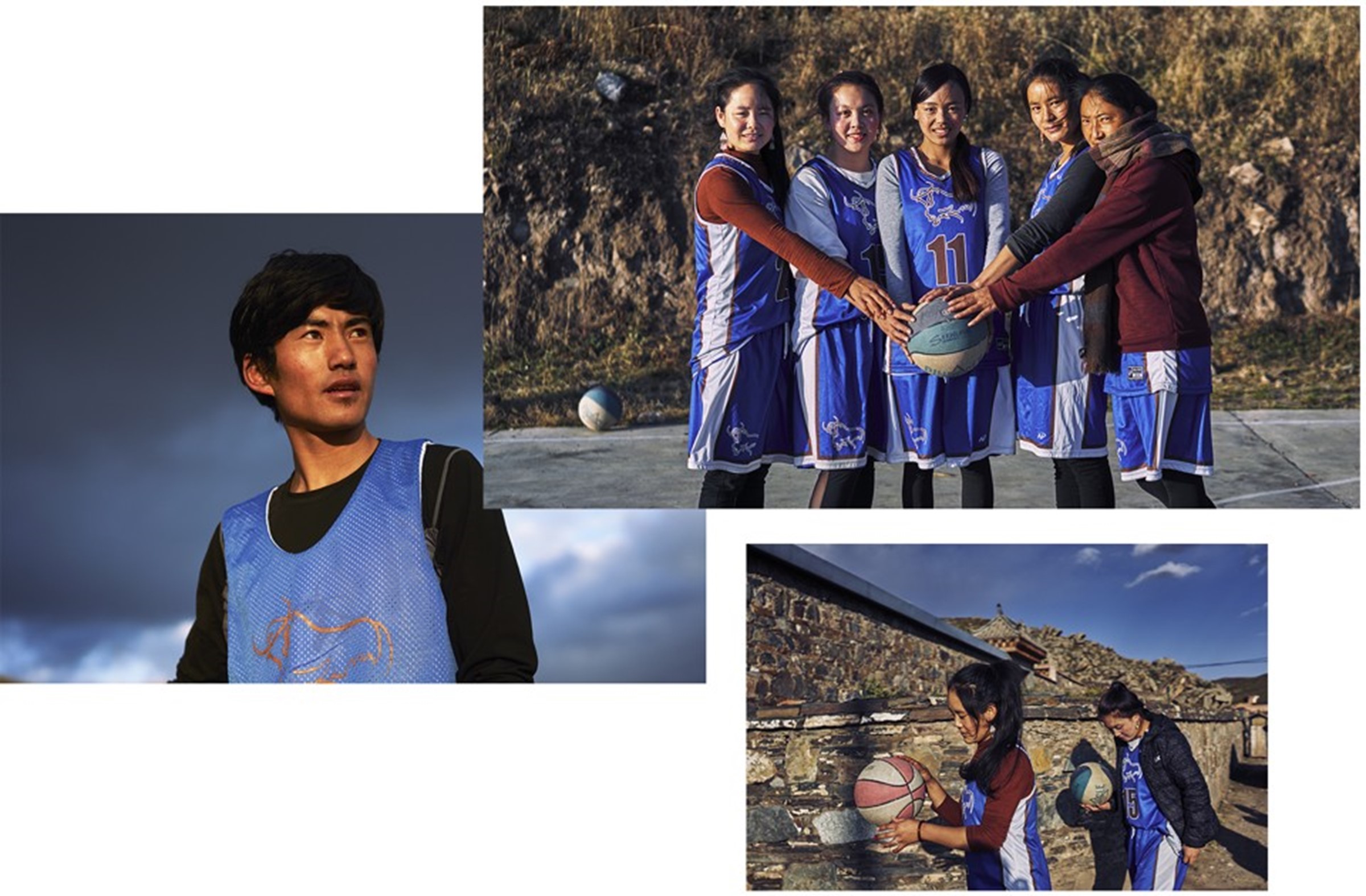

Dugya Bum, who is the best player on the Norlha basketball team. (An Rong Xu)

Dugya Bum was a rebellious, immature employee. He ignored the no-smoking rule and routinely snuck into the guesthouse kitchen to take food. He was transferred to the factory workroom, where he eventually became a dyer. He complained about his pay.

In the felting section upstairs, a quiet, skinny man of 20 named Jamphel Dorjee was having his own troubles. Jamphel had grown up herding animals in a village down the road. He had married a woman in Ritoma, where he didn’t know anyone. His wife worked at Norlha, so he had gotten a job there too. Jamphel was shy, and his workstation was isolated from other employees’. After work, he had nothing to do. But he noticed that every evening, the other male employees played basketball. One night, he followed them to the court. Soon, he was trying to play. But neither he nor Dugya Bum knew that basketball would transform their lives.

Bill Johnson, 32, grew up in Everett, Washington, north of Seattle. In high school, he was into math and theater. But when he sprouted to 6 foot 8, he began to focus on basketball. He could shoot well, but because of his skinny frame, he struggled with rebounding and defense. He wasn’t recruited by any major basketball schools, so he enrolled at MIT. He worked hard at his game, and in 2009, when he was a senior and co-captain, MIT advanced to the Division III NCAA tournament—the first berth in its history.

Norlha coach Bill Johnson (left) and veteran point guard Jampa Dhundup (right). (An Rong Xu)

When he wasn’t on the court, Johnson had a slightly offbeat vibe. He won a school talent show with an interpretive dance involving streamers and tight pink shorts. (“If you’ve seen the movie Napoleon Dynamite, it was almost like that,” Jimmy Bartolotta, an MIT teammate, told me.) Rather than spend spring break in Cancún with his friends, he volunteered to teach dental hygiene in Nicaragua.

After graduation, Johnson became an MIT assistant coach, then played in a league in Costa Rica. “I was nickel-and-diming it,” he says, “barely getting by.” While visiting Bartolotta, who played professionally in Iceland, Johnson partied and drank with fans; soon after, he signed a short-term contract to play there. After that, he went to play for six months in Australia.

In 2014, after a stint playing in Cape Verde, Johnson returned to the United States. His MIT friends were now neurosurgeons and engineers, real-estate investors and CEOs. Johnson—who had grown out his beard, and often bundled his hair into a man bun—had no real career plan. He was scrolling through Facebook when he noticed a post from a cousin in India about a former classmate, Dechen Yeshi, who was hiring a tutor for her young daughter in Ritoma. Johnson began researching Norlha online. When he saw a photo of its basketball court, that “sealed the deal,” Johnson says.

One player sported dress shoes; another, a worn business suit; and another, mittens.

He applied for the job opening and was immediately rejected. Dechen considered him overqualified. Also, she was puzzled by the degree to which his application emphasized basketball. But over the next several months, he emailed repeatedly. Even after the tutor position was filled, Johnson told Dechen he was willing to help the company in any capacity.

Dechen, in turn, researched Johnson online. His persistence and academic credentials impressed her, as did his attitude. So, she invited him to Ritoma to be a volunteer basketball coach for the Norlha team. The ragtag group of Norlha workers occasionally competed in ad hoc tournaments, and she thought Johnson could perhaps instill discipline and teamwork—values that might also benefit the company. Plus, he’d offered to pay his own way. “All I need is a bed,” he’d written.

Left: Dechen Yeshi (center), a co-founder of Norlha, inspects a new product in the company’s workshop. (An Rong Xu)

Johnson arrived in Ritoma in August 2015. The place felt empty: The nomads and their animals were off in the high summer pasture.

At the Norlha guesthouse, where he’d be staying, he met with Jampa, the team’s soft-spoken veteran guard. Jampa, now 30, is also a poet, whose work has been published as far off as Lhasa, some 1,400 miles away. “We want to be the best team in Gannan,” Jampa said. “We can start tomorrow. Tell us what to do.”

At the first practice, about 25 Norlha employees gathered on the court. To them, the moment was surreal: Here stood a professional player from the United States. (“We all thought, NBA,” Jampa recalls.)

For his part, Johnson saw a “hodgepodge of guys.” Most of the players were wearing jeans. One sported dress shoes; another, a worn business suit; and another, mittens. Moments before practice was to begin, there was a roar and a cloud of dust as a motorbike bearing another player screeched to a stop at mid-court. “Holy shit,” Johnson muttered to himself. “What is this?”

Johnson is careful to describe his coaching style as a collaborative effort between himself and the players. Still, he knew what he saw when practice began. Players hogged the ball. They made clumsy attempts at virtuoso dribbling. Shooting forms were askew. “Nothing was right,” Johnson says. “These guys just beat the crap out of each other.”

Johnson’s first impression of Dugya Bum was negative. He had an arrogant vibe, and off the court, he dressed in flashy clothes: big coral necklaces, orange bandannas, porcupine-style hair. His jump shot was herky-jerky, and his skills were underwhelming. But at 6-foot-1, Dugya Bum at least carried himself like a basketball player. He was fast, and he was fluid.

Constantly following Dugya Bum to practice was Jamphel, who admired his co-worker’s athleticism. Unlike Dugya Bum, though, Jamphel, at 5-foot-10, was timid and constantly had the ball stolen from him. His shot resembled an overhead catapult and was wildly inaccurate.

Still, Johnson was enthusiastic as he ran his new players through drills for the first time. Practices, which lasted from 5:30 p.m. until sundown, became must-see events. Villagers brought stools and thermoses of hot water. They laughed when shots were missed and clapped when they went in. They watched as Johnson shouted at his guys and occasionally played alongside them. Sometimes, to everyone’s delight, he would dunk the ball.

Johnson led the players on jogs through the village and sat with them to meditate. During lunch, he had them lift weights—mostly bricks and bags of flour or rice—in the factory courtyard. He showed them film of the San Antonio Spurs, whose style emphasized teamwork. The players called Johnson gegen, meaning “teacher.”

Jampa phoned representatives of rival teams to schedule games. Occasionally, local businessmen sponsored tournaments. Nomadic teams traveled to them by motorbike and camped out in tents. All-monk teams also joined the competitions. Across the region, Johnson noticed, were passionate players without coaches or “any concept of what we would consider organized play.”

At times, the most effective way to guide and motivate his team, Johnson realized, was to play himself. So he suited up for one tournament in August 2016, in a cavernous gym full of cigarette smoke in Maqu, 125 miles from Ritoma. Despite Johnson’s participation, Norlha was overwhelmed by a more aggressive, better-shooting team and lost in the first round of the playoffs. Dugya Bum had scored a few baskets, but he hadn’t played impressively. Johnson had forbidden him to shoot anything but layups because of his faulty jumper. As for Jamphel, “I wouldn’t even consider putting him in,” Johnson says.

With winter approaching, the practice was put on hold until April. Nonetheless, Dugya Bum began messaging Johnson, requesting one-on-one instruction. They met at the court at 6:30 a.m., or during lunch, or before dusk, to run drills and lift weights. Johnson deconstructed Dugya Bum’s jump shot. Jamphel tagged along. Together, over the long, brutal winter, the two teammates worked on their game. Dugya Bum quit smoking. “I’d give up my life for basketball,” he told fellow Norlha employees.

By the summer of 2017, Dugya Bum was a different player. He blew past defenders for easy baskets. He dished the ball off to teammates for assists. His jump shot had improved; he got the green light to shoot from mid-range. With added muscle, he finished more easily at the rim, powering through contact with opposing players. There were moments, Johnson thought when Dugya Bum could have held his own playing New York City streetball.

Players informed Johnson they couldn’t practice because they had to chase mastiffs that were roaming around the village and terrifying people.

Norlha was also playing better as a team. Players no longer ignored their teammates to go one-on-one. Now they worked the ball around for an open shot. At summer’s end, Dugya Bum was selected as an all-star to play in Gannan’s annual tournament. Afterward, he was named one of Gannan’s top 10 players.

In the workroom, meanwhile, Dugya Bum’s attitude had improved. He made eye contact with co-workers and talked more openly. Basketball had helped him “find meaning,” Dechen Yeshi, who called him a “model employee,” told me. By this time, he had also married Lhamo Tso, the Norlha model.

Jamphel had also progressed on the court and was earning minutes. He was a more adept ball handler, had improved his court awareness, and made open shots. But what Johnson admired most were his intangibles: Whatever Johnson asked him to do, he did without hesitation.

Even more significant was Jamphel’s evolution off the court. The once-quiet young man was now opening up to teammates. “We’ve become best friends,” Jamphel recently said of them.

Jamphel’s wife, Jamyang Dolma, works at Norlha as a tailor and a model. Like other nomadic women suddenly thrust into a 9-to-5 job, she had found the concept of free time after work completely alien.

For women especially, nomadic life is difficult. Days are long and dominated by chores: starting fires, milking animals, chopping wood, churning butter, cooking meals, collecting dung for use as fuel, cleaning pots, caring for children. The idea of a hobby never came up. “In traditional life, women don’t play basketball, but it doesn’t mean women don’t like it,” Jamyang Dolma told me. “It may be because they never had the opportunity or anybody to lead them.”

In 2016, a female Norlha employee, Wandi Tso, asked Johnson whether women at the company could form a team.

“Whenever you want to play,” Johnson told her, “let’s do it.”

The women who signed up were initially too afraid to even catch the ball. But as they learned the fundamentals, their confidence rose. Their shooting form was generally “textbook,” Johnson says, unlike the men’s, whose years of bad habits had to be trained out of them. Villagers in Ritoma gradually grew accustomed to seeing women on the court.

Dugya Bum and Jamphel helped Johnson train the women’s team, which included both of their wives. Lhamo Tso became the team’s best all-around player, and Jamyang Dolma the team’s best shooter. At home, she and Jamphel would discuss the drills they’d worked on that day.

Left: Jamphel Dorjee, the most improved player on the men’s team. Above right: Players from the Norlha women’s team, including Lhamo Tso (far left), the team’s best all-around player, and Jamyang Dolma (second from right), the team’s best shooter and Jamphel Dorjee’s wife. (An Rong Xu)

In September 2017, the Norlha women played competitively in front of the villagers, in a three-on-three tournament organized by Johnson. Wearing light-blue jerseys, the Norlha players giggled each time they blundered and clapped whenever their team scored.

When I was there, I watched one of the women’s team’s practices. Two female coaches were visiting for the week: Ashley Graham, a former professional player in Europe who owns the training group Pinnacle Hoops, and Carly Fromdahl, a Pinnacle instructor who played college ball at Seattle University. They ran the Norlha women through drills, including layup lines (the women dribbled slowly but made most of their shots), ball-handling exercises, and chest-and-bounce passes.

Basketball, Dechen told me, has become a “gateway for the women to try new things.” They started doing yoga and meet regularly outside of work. They eat meals together now and have begun discussing their jobs, lives, and plans for the future.

Basketball has “made them more courageous,” Dechen said.

For the men’s team, however, hurdles began to emerge. At MIT, Johnson had considered practice time sacred—something to be missed only because of serious illness or a family member’s death. In Ritoma, Johnson scheduled mandatory practices three days a week. But aside from Dugya Bum and Jamphel, attendance was spotty. Once, Johnson’s players informed him they couldn’t practice, because they had to chase after fearsome Tibetan mastiffs that were roaming around the village and terrifying people. Another time, they said they couldn’t practice because they had been up all night circumambulating the village monastery, a Buddhist ritual performed to accumulate merit toward future rebirths. Often, players had to help relatives with nomadic duties, such as finding lost sheep.

So early in the 2017 season, Johnson set a benchmark: To play in a major tournament in Maqu scheduled for August, the team was required to hold 20 practices with at least 10 players in attendance. But at summer’s end, the standard hadn’t been met. At a team meeting, Johnson said Norlha wouldn’t play in Maqu. (He later discovered that multiple players had joined the team solely for the trip, during which they would have been able to skip work and stay in a hotel.) All but three of the players quit. The holdouts: Dugya Bum, Jamphel, and Jampa.

Soon afterward, Johnson and Dechen met to discuss the program’s future. Norlha’s team was open only to employees, and it had become clear that the company’s 120-person workforce was not a large enough pool from which to draw a committed squad. During their chat, Johnson noted that among the villagers who didn’t work at the factory were many good players who were eager to train but had no coach.

Korchen Kyap, for example, was a 23-year-old nomad who had proved to be one of Ritoma’s best players—6-foot-2, with excellent leaping ability. Throughout the previous winter, when Johnson returned to the United States to visit family, Korchen Kyap and other nomads who had been playing without a coach flocked to Norlha’s court daily for pickup games, braving the ice and snow. But during the summer, the heart of the basketball season, it was impossible for Korchen Kyap to play with the team, even without Norlha’s employees-only rule. The up-mountain pasture to which he herded his animals each morning was too far from the village center for him to return for practice at 5:30 p.m.

Dechen had seen how Johnson’s brand of team-first basketball had brought Tibetans together, spread the Norlha name, and raised revenue by earning cash prizes—anywhere from the equivalent of several hundred to several thousand dollars—at tournaments in the region.

So Dechen decided to open up the team to the nomads—and pay the players. She set aside an annual budget of 145,000 yuan, or about $21,000. Two players, Dugya Bum and Chökyong Kyap—a fiery, talented guard from the White Horse Clan—would become full-time basketball players, with Dugya Bum earning a monthly salary of 2,500 yuan (about $365, or four times the average local income) and Chökyong Kyap earning 2,000 yuan. Eight players making 1,000 yuan a month would round out Norlha’s traveling team. Five practice players, including three developmental players, would earn 500 yuan apiece. (Johnson himself was now earning a salary as Norlha’s e-commerce manager, a job he’d taken on in 2016.)

Johnson is hoping to eventually add monks to the team. Ritoma’s best monk player is Dugya Bum’s brother, Sonam Drakpa. (He is the backboard-shatterer I saw in the video on Norlha’s Facebook page.) He and two other monks—Korchen Kyap’s brother and a 6-foot-4 bruiser named Sherab—scrimmage with Norlha during the monastery’s brief summer break. But as far as playing full-time, “it’s tough with the monks’ schedules,” Johnson told me sadly.

Photographs were taken in October 2018 in Zorge Ritoma (An Rong Xu)

I wasn’t the only visitor who had planned to attend Johnson’s Norlha Basketball Invitational and Tibetan Hoop Exchange. Eight other Americans made the trip as well, including four basketball players: Graham and Fromdahl from Pinnacle Hoops; Andrew Greenblatt, a former Division III men’s basketball player at Swarthmore College who had helped Johnson raise funds for the tournament; and Isaac Eger, a writer who was traveling the world playing pickup basketball. Johnson had arranged for some low-key pickup games against monks in the region. Building relationships with them, he said, is “priceless.”

With this in mind, Johnson planned a scrimmage with the top team from Labrang, one of Amdo’s largest monasteries. But first, we were given a tour. Pressed up against a big green mountain, the monastery’s white, red, and yellow structures, some with gilded roofs, are connected by a labyrinth of dirt alleyways through which monks and pilgrims roam. A monk leading tours collected my ticket stub, crumpled it up, and tossed it into a trash bin. “NBA,” he said, bumping my fist.

The day of the scrimmage, as we drove along a narrow mountain pass, Johnson warned our group of Labrang’s physicality and offered an advance apology: “No one’s purposely trying to hurt you,” he said. “They’re still Buddhist.” (I’d intended to play but was sidelined after pulling a muscle the previous day while demonstrating a jump hook.)

We made a winding descent into a valley, then turned off the road and drove unsteadily on rocky grasslands. The court appeared, its weathered surface riddled with cracks and wet spots. A stream flowed alongside it. In all directions, empty plateau stretched for miles.

A green taxi wobbled up behind us. It stopped shy of the water’s edge, and several 20-something monks in robes got out, holding bags and basketballs. More taxis followed, also filled with monks. The men vanished into a nearby hut and emerged wearing basketball gear, including white “USA” jerseys. They splashed across the stream and onto the court.

The athleticism and creativity of Labrang’s players were immediately evident. They hung in the air on jump shots and made Kobe Bryant–esque fadeaways. They played hard, and they fouled hard. At one point, Greenblatt got clocked by the opposing point guard and fell. “They don’t mean any harm!” Johnson shouted.

A stray ball rolled onto the court, and some of the Americans stopped playing. Labrang seized the chance to make an uncontested layup. “Guys!” Johnson shouted, “There’s gonna be hawks, vultures, balls rolling onto the court—you gotta play through!”

The teams played two games to 20, and both went down to the wire. The monks won the first one, 20–19. The second went to the Americans, 20–18. After that game, Greenblatt, Graham, and Fromdahl sprawled onto the court exhausted, unaccustomed to playing at that altitude.

“These guys are tough,” Johnson said.

“Super tough,” Greenblatt replied.

The Norlha basketball team prepares for a game against the Sichuan All-Stars at a tournament in Hezuo, the capital city of the Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. (An Rong Xu)

Although the Norlha Invitational tournament had been postponed, Johnson was still planning to lead, with the visiting Americans, several days of clinics for Norlha’s teams. But after the first day—a cool, sunny afternoon of spirited drills and pickup games—Johnson received more bad news: False rumors had reached the Public Security Bureau that the Americans, me included, were NBA players; apparently worried that our presence would attract large crowds, the authorities urged the Norlha team to stay away from the court. All remaining basketball activities were called off.

The following day, a damp snow fell, blanketing the court. Entire streets were reduced to mud. The village was quiet.

I took the opportunity to visit Dugya Bum’s house. I walked through his front gate into a muddy outer courtyard, and then into a room with a red carpet and wood-paneled walls. Displayed high on one was an elegantly framed picture, bordered by Tibetan letters, of LeBron James in front of a grasslands backdrop of horses and mountains. Basketball trophies were perched on a shelf.

Sipping butter tea, we spoke about his dream, nearly realized, of making a living playing basketball. When I asked him what his life would be like without hoops, he chuckled uncomfortably, then paused. “If basketball disappeared,” he said softly, “my love would be finished. Everything would be finished.”

Shortly after I left the plateau, good news arrived at last: A monk had built a new gymnasium in Hezuo, the capital city of Gannan, 16 miles away, and there would be a tournament in late November. In a preliminary-round game, Norlha faced the Zorge All-Stars, a brutally physical, all-nomad team. Norlha lost in overtime by one point. But the team won its three other matchups, qualifying for the playoffs.

Norlha won a quarterfinal rematch against Zorge, 48–39. In the semifinals, Norlha defeated a university team from Zhuoni County by one point, setting up an evening final against White Khata, a team featuring standout players from across the vast Amdo region.

Before sunrise on the day of the championship, Norlha’s players rode their motorbikes up to Amnye Tongra, Ritoma’s highest peak. They made offerings of sugar, barley, and fruit to the mountain deity believed to protect Ritoma and shouted, “Lha gyal lo!“— “Victory to the gods!”

A large contingency of Ritomans—nomads, monks, and Norlha employees—drove to Hezuo, where fans of both teams squeezed into the tiny, high-ceilinged gym, stuffing it beyond capacity. Fans bled onto the court; some climbed up the basket supports. Norlha wore its standard blue jerseys; Khata wore red. On the walls behind the baskets hung billboard-size posters of Kobe Bryant and LeBron James.

Eventually, officials locked the gym door; outside, latecomers climbed onto one another’s shoulders and peered in through the windows. Back in Ritoma, in the monastery and in households alike, people huddled around their smartphones, which were illuminated with shaky video feeds of the match.

When the game began, Dugya Bum seemed overhyped and anxious. On his first offensive touch, he rose up for a 10-foot jump shot that clanked long off the backboard. Twice in the ensuing minutes, he turned the ball over.

Meanwhile, Khata’s blazing-fast guards penetrated at will. The score, indicated on a small flip-style board at center court, seesawed back and forth. At halftime, Norlha led 18–16.

In the second half, Dugya Bum’s nerves settled. He soared in for rebounds and, low in his defensive stance, kept Khata’s ball handlers at bay. Norlha led 28–24 entering the final quarter.

Johnson hopes that his team will become so well-respected that it will attract players from across the Tibetan plateau. (An Rong Xu)

Khata bounced back, tying the score and then taking a narrow lead. In the waning minutes, with Norlha trailing 36–35, Johnson hit a three-pointer from the top of the key. Khata replied with a three of its own and followed that with a lay up to pull ahead by three. A Norlha player then made one of two free throws to cut the lead to two.

But that was as close as the team got. In the final seconds, there was scrambling and desperation from Norlha. Whoops and hollers filled the gym. But the clock wound down. A horn rang and Khata fans burst onto the court. Norlha had lost 41–39. Dugya Bum kneeled on the floor and covered his eyes, hiding tears.

Johnson huddled his team close. “We played our hearts out!” he shouted. “I know this hurts. But use this hurt, this feeling that you have right now, to fuel you over the winter.”

Jampa drove Johnson and Dugya Bum back to Ritoma. Dugya Bum was in the back seat, silent. It was almost midnight when they arrived back in Ritoma. Jampa dropped off Dugya Bum and Johnson at Norlha’s gate.

In a few months, Johnson would move out of the guesthouse and into his own place in the village. “I’m still scratching the surface of this way of life, this culture, Buddhism,” he told me, adding that he’s “definitely here for the long haul.”

Johnson’s vision for Norlha basketball is to build a program so well respected across the plateau that the best and most driven players will flock to train in Ritoma and then return to their towns and villages as player-coaches to spread what they have learned. Johnson knows achieving this goal is in large part dependent on Dugya Bum: If his commitment remains steadfast, Johnson believes he could become one of the best players in all of Tibet.

It was with these aspirations in mind that Johnson, late that night after their championship loss, gathered his thoughts as he and Dugya Bum stood together in the darkness. Before heading their separate ways, they embraced. Then Johnson looked Dugya Bum in the eye. “What you’ve done this last year was amazing,” Johnson said. “But keep it going. You’re our leader now. This is just the beginning.”

Support for this article was provided by a grant from the Pulitzer Center. It appears in the January/February 2019 print edition with the headline “How Tibet Went Crazy for Hoops.”