TIBET EQUILIBRIUM vs THUCYDIDES TRAP – UNFINISHED VIETNAM WAR

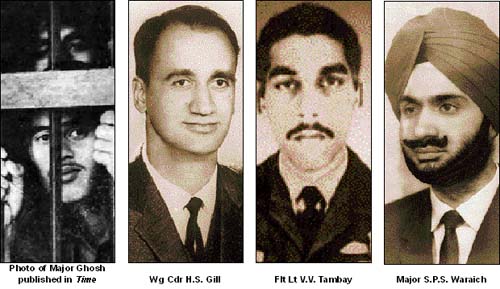

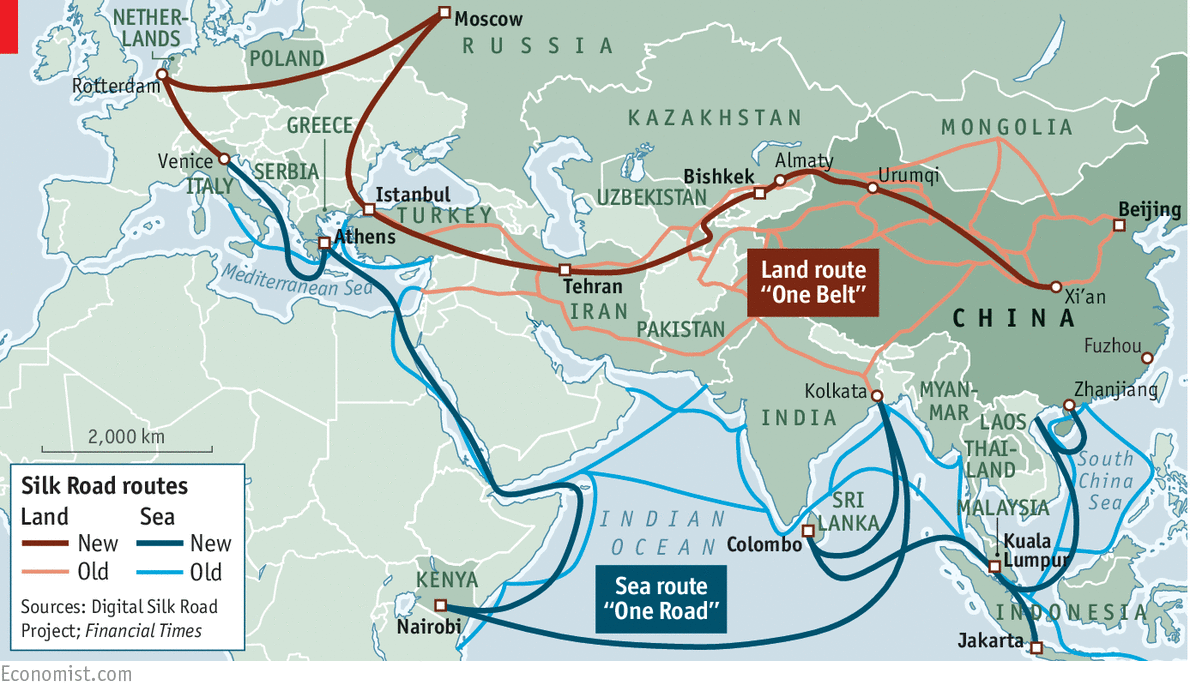

Special Frontier Force represents military organization that symbolizes ‘Unfinished Vietnam War’. The US fought bloody War in Vietnam to contain, to engage, to confront, and to oppose the spread of Communism in South Asia. Red China’s Evil actions Destined US-China War. ‘Tibet Equilibrium’ is good reason to fight Unfinished Vietnam War to its rightful conclusion.

Rudranarasimham Rebbapragada

Could the U.S. and China end up in a terrible war that neither wants?

May 30 at 6:00 AM

Chinese troops marching to commemorate the 70th Anniversary of the ‘Victory of Chinese People’s Resistance against Japanese Aggression and World Anti-Fascist War’ at Tiananmen Square in Beijing on Sept. 3, 2015. China planned to increase its defense budget in 2016 by 7 to 8 percent (European Pressphoto Agency/Rolex Dela Pena/poll/file)

Is a dangerous pattern emerging in U.S.-China relations? International relations scholar Graham Allison coined the term “Thucydides Trap” in 2012 to explain how a rising power can instill fear in an existing power, leading to hostility and mistrust that can escalate into war.

In his new book, Allison argues that China and the United States are falling into this trap, which owes its name to Greek historian Thucydides’s famous history of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, which proved disastrous for both sides. Fast-forward a couple of millennia, and some observers worry that Washington and Beijing are heading toward the same fate.

But the focus on whether the United States and China will follow this path has obscured another insight from Thucydides’ classic work, “The Peloponnesian War” — how the geography of East Asia would shape what a U.S.-China war might look like, and just how dangerous and destructive such a war may be.

There is another way to look at rising powers

The Thucydides Trap we often see in debates about rising powers is actually a simple version of power transition theory, which dates back to the 1950s. The idea is that a war between great powers is more likely when a rising state seeks to topple the international pecking order. It is easy to see why this idea might be applicable to contemporary U.S.-China relations.

There are other ways to view the situation. Some scholars have argued that things may be more stable when two leading powers are at similar strength; others argue that the sources of war lie elsewhere. And the empirical record does not provide a lot of evidence that rising and dominant powers fight directly, or for the reasons that power transition theorists suggest. This leads some scholars to suggest that the power transition model is a poor guide to understanding U.S.-China relations.

None of this discussion means that U.S. and Chinese analysts should ignore Thucydides, although perhaps they should look for inspiration from other parts of his book.

The other Thucydides Trap isn’t pretty

Thucydides is best remembered for his short argument about the causes of war, but he said much more about its conduct. His insights are quite relevant for a hypothetical clash between the United States and China. This is especially the case in his commentary on the first few years of the Peloponnesian War, where he describes how Athens and Sparta stumbled into a protracted fight that neither side expected.

How they got there has to do with a very different kind of Thucydides trap. They wanted a quick victory, and they wanted to avoid their respective enemies’ comparative military advantages. Both opponents fell victim to delusions about bloodless victory without hard fighting. After their early efforts failed, they faced a terrible dilemma: capitulate or settle into a long and uncertain war.

And both sides faced the same basic challenge when the war began in 431 B.C. — how to avoid engaging on terms that favored the enemy. Sparta (like China today) was a dominant land power while Athens was the dominant naval power (like today’s United States). Sparta needed to figure out how to defeat Athens without challenging its navy directly. Meanwhile, Athens needed Sparta to concede without taking the risk of a pitched battle on land against the formidable Spartan army.

Neither side had a good solution — but they pursued operational fantasies about how to win without having to challenge the enemy’s main area of strength. Athens wanted to use its navy to assist land forces that would conduct raids on Sparta’s allies, while simultaneously encouraging a slave insurrection in the Spartan homeland. Sparta, for its part, thought that others would take on the Athenian navy on its behalf — and then it could focus instead on fighting on land.

Not much came out of these plans for the first few years. As long as Sparta and Athens were unwilling to challenge their counterparts directly, neither was able to hurt the enemy enough to force surrender. Neither side was willing to back down. And because they could both retreat to reliable sanctuaries — Sparta on land, Athens at sea — they didn’t need to seek terms.

A toxic blend of geography and politics conspired against the Greek great powers, and the result was an exhausting war that no one wanted. Geography enabled retreat, while political pressures encouraged continued fighting. Meanwhile the military balance held, with Sparta dominant on land and Athens controlling the water. What followed were years of costly but indecisive campaigns. Neither side was strong enough to win — nor weak enough to lose.

Geography would factor into any U.S.-China war

Here’s how this applies to U.S.-China relations today. As I explain in a forthcoming article in the Journal of Strategic Studies, the United States and China risk slipping into this pattern.

War is far from inevitable, of course. But if it did break out, the United States and China — like Athens and Sparta — would each be able to retreat safely in the event of early wartime setbacks. When we read about potential flash points that could spark a confrontation, especially over Taiwan and disputed maritime claims, this geographic risk lurks in the background.

Wartime setbacks that send each side retreating to its safe haven are possible, perhaps even likely, given that both sides are placing their bets on elaborate plans to win quickly. In this scenario, China and the United States would each put a premium on interfering with the other’s communications and blinding its intelligence capabilities to inject confusion on the battlefield and make it hard to coordinate complex operations.

For the United States, the goal would be to seize the initiative, ensuring freedom of movement in the waters near the Chinese mainland, overcoming anti-access weapons, and buying time for superior reinforcements to arrive in the region. For China, it means forcing the United States to fight farther from the shore, which might prevent it from effectively defending its regional allies and partners.

These plans might sound good in theory, but both sides are investing in efforts to secure their communications against debilitating attacks. The normal fog and friction of war also work against operational plans that depend on precise attacks with little margin for error. Leaders might also become so concerned about nuclear escalation that they scale back their opening moves, further decreasing their effectiveness. For all these reasons, both sides may end up disappointed by the result of the first volley.

A quick political settlement might be the rational response in this case, but the fact that both sides were willing to take the gigantic risk of war suggests they will find it hard to stomach the prospect of backing down, especially if they haven’t suffered many casualties. This is a recipe for a long and grinding war.

This is the kind of Thucydides trap that looms over any U.S.-China conflict. Geography, politics and the maritime-land balance in East Asia create a situation likely to lead to prolonged fighting. The central task for strategists is figuring out how to escape it. If they cannot, the only alternative is avoiding war in the first place.

Joshua Rovner holds the John Goodwin Tower Distinguished Chair in National Security and International Politics at Southern Methodist University, where he also serves as director of the Security and Strategy Program (SAS@SMU).

Comments

Rudranarasimham Rebbapragada

10:32 AM EDT

On behalf of Special Frontier Force, I confirm the possibility of war between the US and China. We wanted to fight this War to relieve pressure on the US Armed Forces fighting bloody war in Vietnam. President Nixon-Kissinger continued using bombing campaign while knowing that it was not effective. Special Frontier Force as a military organization symbolizes the Unfinished Vietnam War. US was fighting against the spread of Communism in South Asia. The fall of Soviet Union has not eliminated the problem of Power Equilibrium in Asia. If not the tensions of South and North China Sea disputes, the great problem of ‘Tibet Equilibrium’ will be a good reason to check, to contain, to engage, and to oppose Red China.

mustquestion

10:20 AM EDT

Odd that it does not include North Korea in the discussion. The most likely scenario is a US – N. Korea conflict with China taking sides with N Korea. But that does not fit the simplistic model of dominant vs challenging state that is the book’s theme.

Rudranarasimham Rebbapragada

10:46 AM EDT

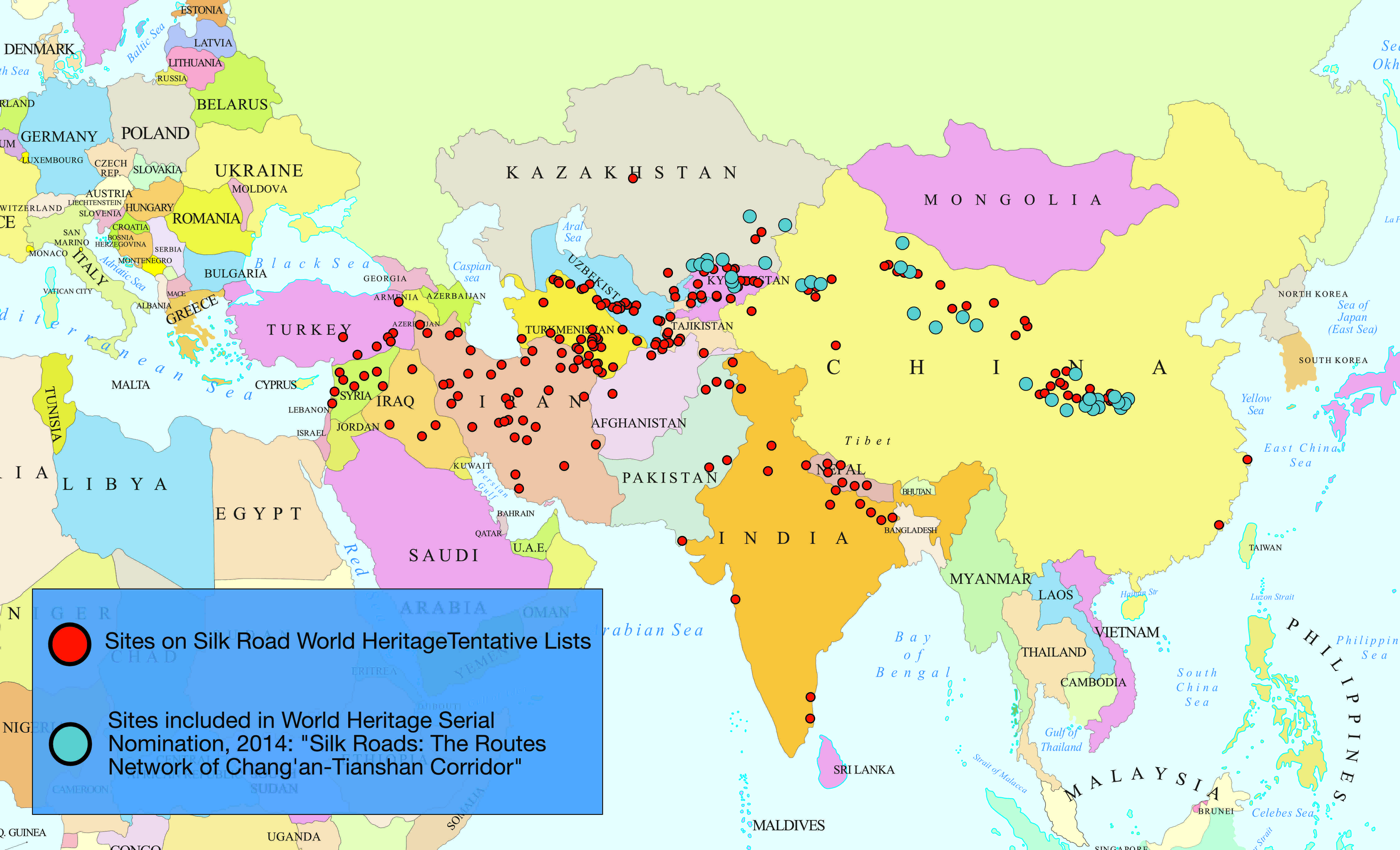

Tibet is the second largest nation of this region sharing border with China. In terms of size, Tibet is second to China. Korea receives plenty of media attention. The problem of Balance of Power demands action to accomplish ‘Tibet Equilibrium’.

nqb123

7:54 AM EDT

I don’t see how the US and China could stumble onto war. What’s the motive for a war when there is so much trade going between these 2 countries? There is no common border between the two, no known historical animosity between the two people, no known problem that only a war could solve. The Taiwan problem is likely to be solved sometime in the future by the Chinese themselves. If the US wanted to defend Taiwan in the first place, Taiwan and the US would already have a mutual defense treaty. I don’t see any US military base in Taiwan either.

Rudranarasimham Rebbapragada

10:52 AM EDT

That’s not correct reading of the US history. President Harry Truman tried his best to avert Communist victory in China. Apart from giving support to Nationalists, the US made modest efforts to deliver arms and ammunition to Tibet during 1948-49. Tibet maintained policy of Isolationism until China’s military conquest in 1950s. Since that time, the US is helping Tibetan Resistance. The plans for a future war are not yet buried.

Douglas Levene

7:42 AM EDT

Excellent article, thank you. I’ve been teaching in China for the past seven years and worry about what to do if war breaks out – can I make it across the border into Hong Kong? Would the Chinese expel all Americans or intern them or worse? From this end of the pond, it’s pretty easy to see how rising Chinese confidence could lead to miscalculations, spilled blood and war. The Chinese think they can overcome US supremacy in submarines by building out a huge network of sea floor sensors in the South China Sea – who knows what that type of arms race combined with territorial expansion could lead to?

kcs1760

7:22 AM EDT

A good article, but I would have liked to read how the author feels our economic inter-dependency would factor into the equation.

Rudranarasimham Rebbapragada

10:56 AM EDT

In the past, Communist Powers like Soviet Union encouraged people and nations to oppose European Colonial Rulers. Now, the world of geopolitics and geoeconomics have changed. Now, the US would encourage people and nations to oppose Red China’s Neocolonialism.

William Billeaud

7:10 AM EDT

Only someone with a worldview based in the capitol of the U.S. Bible Belt would spew this. What horse shout; I subscribed to Wash Post for this?

Rudranarasimham Rebbapragada

11:00 AM EDT

Don’t worry about your subscription. You can still read this story without being a subscriber. The realities of the world are described by Red China’s occupation of the second largest nation of South Asia. As long as that occupation prevails, there will be Power Imbalance. Tibet Equilibrium cannot be dismissed as wishful thinking.