Tibet Consciousness – The Undying Hope for Freedom

On behalf of Special Frontier Force, Establishment 22, I host the Living Tibetan Spirits. These are Spirits of young Tibetan soldiers who lost their lives with the hope for Freedom in Tibet. We have not given up on our hope.

At Special Frontier Force, the concern is not about scoring a military victory. Occupation of Tibet is unjust, is illegal, and we stand opposed to it and resist as best as possible. Victory in War is not always decided by relative strengths of parties involved. Red China’s act of aggression is Evil and hence Red China is destined to fail.

Hope for Tibet’s Freedom comes from a belief that predicts Red China’s sudden downfall similar to fall of the Evil Empire identified as Babylon in Revelation, Chapter 18.

I am pleased to share a story published by Nolan Peterson, foreign correspondent of The Daily Signal. Hopefully, media will give attention to the foul game played by Nixon-Kissinger during 1970-72. Special Frontier Force/Establishment 22 initiated Liberation of Bangladesh with military action in the Chittagong Hill Tracts in response to Genocide in East Pakistan. India’s Prime Minister Mrs. Indira Gandhi met US President Richard M Nixon in Washington DC on November 03/04, 1971 to enlist his support for India’s military intervention in East Pakistan. President Nixon announced his plan to visit Communist China on July 15, 1971. I call it as “Black Day to Freedom” and characterize Nixon as Backstabber of Tibet. I have known Richard M Nixon and his association with Tibetan Freedom Movement during the years he served as US Vice President during the presidency of Dwight David Eisenhower. Later, President Nixon denied support to India and Tibet for he needed help of General Yahya Khan, Pakistan’s military dictator to befriend Chairman Mao Zedong of Communist China who was known for his crimes against humanity including killing of millions of innocent civilians during infamous Cultural Revolution. I may not agree with Nolan Peterson’s analysis of events, but it doesn’t really matter. The only thing that matters to me is that of hosting undying hope for Freedom in Tibet.

Rudra Narasimham Rebbapragada

Ann Arbor, MI 48104-4162 USA

Special Frontier Force-Establishment 22-Vikas Regiment

A CIA-Trained Tibetan Freedom Fighter’s Undying Hope for Freedom

NOLAN PETERSON @nolanwpeterson October 13, 2015

Tsering Tunduk fled Tibet in 1959 after Chinese soldiers executed his parents. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

PANGONG LAKE, India—At dawn, the old man stood outside his home on the Indian side of Pangong Lake, thumbing his prayer beads and chanting, “Om mani padme hum.”

The sun was rising from behind a wall of Himalayan peaks on the opposite shore, which was Tibet.

The old man’s face, which had been darkly tanned by a lifetime in the high-altitude sun, was as carved and as wrinkled as the Himalayas. His mouth moved almost imperceptibly as he chanted his mantra and stared across the burning blue water toward his homeland, from which he has been exiled for more than half a century.

The old man, whose name is Tsering Tunduk, fled Tibet in 1959 with his little sister, Khunda, after Chinese soldiers executed their parents. It was the same year the Dalai Lama escaped Chinese artillery in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa to seek exile in India.

Orphaned and alone, Tunduk and his sister joined a group of refugees for a treacherous two-month-long journey across the Himalayas into India. Along the way they faced hypothermia and frostbite, a lack of food, and persistent attacks by Chinese troops. Once they arrived in India, the two children began the hard life of refugees.

Ten years later, after he had completed his studies in Mussoorie in 1969, Tunduk volunteered for a secretive all-Tibetan unit in the Indian army called Establishment 22, which the U.S. CIA helped stand up and train when China attacked India in the 1962 Sino-Indian War. Tunduk went through six months of basic training, which included jump training taught by CIA instructors, whom Tunduk remembered as “blond and tall.”

As a new recruit Tunduk made only 80 rupees a month (when he retired in 1996 he made 1,300 rupees a month, about $20), but life in the military offered Tunduk an opportunity more valuable to him than money.

Pangong Lake, which is 83 miles long, forms part of the border between India and Tibet. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

“China killed my parents, and I wanted revenge,” Tunduk, who is now 70 years old, said during an interview from his home on Pangong Lake. He spoke in halting, accented English as he peeled potatoes in preparation for dinner. A CD playing the Buddhist, “Om mani padme hum,” mantra set to music was on an endless loop in the background. A shrine to the Dalai Lama, draped in a Khata scarf and with offerings of fruit laid out before it, was on a shelf over the table.

“I would have fought them with a knife at that time,” Tunduk added, not looking up. “I wanted to kill them all.”

Even now, at 70, Tunduk says that when he closes his eyes to sleep at night, he is haunted by images of his dead parents. As he describes their murder, Tunduk’s face muscles relax. His usual smile is replaced by something cold and expressionless. His mind is back in a time and place that no words, not even from one’s native tongue, have the power to faithfully recreate.

Tunduk grew up in an area called Nangchen, in the Kham region of Tibet. “They went through my village to get to Lhasa,” he said.

Tunduk’s father was the village boss, he explained, and when the Chinese soldiers took over, they hauled his father and mother into the town square where the soldiers had gathered all the villagers for the Thamzing, or “struggle session”—a public spectacle used to humiliate, torture, or execute Tibetans who oppose Chinese rule.

The Chinese soldiers tied Tunduk’s father’s arms and legs behind his back, beat him, and then shot him in the head. Next, they painted a target in charcoal on Tunduk’s mother’s chest, suspended her by her arms from two wood poles, and used her for target practice, pumping her body with bullets long after she was dead.

The Chinese soldiers made Tunduk and his sister watch. “I cried, and my sister cried,” he said. “There was nothing left to do but cry.”

Tunduk remembers looking into the faces of the Chinese soldiers and seeing nothing—neither pleasure nor pain. It was as if they had no emotions, he said.

A SECRET WAR

After China invaded Tibet in 1950, a grassroots resistance movement sprang up across the Himalayan kingdom. By 1956, tens of thousands of Tibetans were fighting an insurgency against Communist China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA). These bands of guerrilla warriors, mainly comprising Tibetans from the eastern Kham region (known for its fierce warriors and bandits), coalesced into a resistance army called the Chushi-Gangdruk, which Tibetan resistance leader Gompo Tashi headed. The Chushi-Gangdruk (which translates to “Four Rivers, Six Ranges,” signifying unity among all the regions of Tibet) played a key role in the Dalai Lama’s escape from Tibet in 1959. The resistance army also provided armed escorts for the tens of thousands of refugees who followed in the exiled leader’s footsteps to seek sanctuary in India and Nepal.

The Chushi-Gangdruk fought the modern, mechanized Chinese army on horseback, wielding swords and World War I-era weapons such as British .303 Lee-Enfield rifles. Their fighting spirit and tactical successes eventually spurred the CIA to begin an operation in 1957 to airdrop supplies and train hand-picked fighters as paratroopers at secret bases in Saipan; Camp Hale, Colorado; and Camp Peary, Virginia—at a CIA training facility also called the “farm.” The Tibetans’ training was eclectic, including espionage tradecraft, paramilitary and small unit combat tactics, and Morse code and radio communication. The CIA operation to train and assist Tibetan fighters was code-named ST CIRCUS, and the over flights and airdrop missions were named ST BARNUM.

Over the span of the CIA’s secret war in Tibet, which lasted until 1972, Tibetan agents were dropped into Tibet from aircraft ranging from World War II B-17s, which were painted all black, to C-130s from secret bases in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). At first the CIA used East European pilots whom the CIA had previously recruited to drop anti-Soviet operatives into Ukraine. The idea was that the East European pilots would give the U.S. plausible deniability of its involvement if an aircraft went down. Later flights, however, used Air America aircrews and U.S. Forest Service smokejumpers the CIA recruited as jumpmasters and loadmasters. Special U-2 spy plane flights were also ordered to provide more intelligence about the geography of inner Tibet, much of which was still uncharted in the 1960s.

The CIA’s Tibetan operation ultimately failed to make a large-scale impact on the Chinese occupation, and many of the CIA-trained Tibetan fighters were killed in combat or captured. But the operation scored a few key tactical victories and raised the morale of exiled Tibetans. It did create an awkward situation for the Dalai Lama, however, who owed his life to the Chushi-Gangdruk warriors but was also trying to court the favor of the Indian government to secure a home for his exiled nation—backing a secret CIA war in Chinese-occupied Tibet was not in India’s interest at the time.

The CIA continued training Tibetan freedom fighters in Colorado until 1964. And support for Tibetan guerrillas based in the Mustang region of Nepal continued until President Richard Nixon’s normalization of relations with China in 1972.

Yet after CIA support dried up, approximately 10,000 Tibetan guerrilla fighters continued serving in Establishment 22.

Tunduk, third from left, during jump training with the Indian army. (Photo: Shared by Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

In 1962, the CIA’s Tibet operation was in limbo. The Kennedy administration questioned the utility of the mission due to the botched Bay of Pigs invasion and a budding rapprochement with India—Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was reluctant to support Tibet in a way that might antagonize China. The Dalai Lama’s presence in India and the CIA’s recruitment of Tibetan fighters from refugee communities made the CIA’s mission in Tibet a political liability for India’s fragile relations with Beijing.

But the political calculus for both the U.S. and India changed on Oct. 22, 1962, when China attacked India along the Himalayan frontier. India scrambled to mount a military response as 25,000 PLA troops invaded over the Thang La Ridge. Nehru’s longstanding efforts to downplay the Tibetan situation to appease Beijing were exposed as misleading, and he faced scathing criticism at home. Humiliated, Nehru turned to the U.S. to help stand up an all-Tibetan guerrilla warfare unit, tapping into the CIA’s existing recruiting and training networks for the Chushi-Gangdruk mission.

The original purpose of Establishment 22 was to use Tibetans’ fighting prowess and genetic ability to physically perform at high altitude to wage a guerrilla war against China in the Himalayas. Initially, the CIA provided much of the unit’s weapons and training. But the 1962 Sino-Indian War cooled before the Tibetan unit could be trained and fielded. India, however, recognized the combat potential of the unit and kept it active. The unit deployed to combat for the first time in East Pakistan (in hot and humid lowland conditions) in 1971 as part of Operation EAGLE, and later faced Pakistani troops in the Himalayas. Establishment 22, however, never officially faced Chinese soldiers in combat.

The use of Tibetans in operations against Pakistan was controversial among the Tibetan exile community. But the government in exile in Dharamsala ultimately supported the move out of deference to their Indian hosts. The U.S. opposed Establishment 22’s operations against Pakistan. But in 1975 the CIA rekindled its support for the Tibetan unit, sending two airborne advisers to train the Tibetans in high-altitude parachute jumps, using drop zones in Ladakh.

India later tagged Establishment 22 for counterterrorism operations. Based in Chakrata, Uttarakhand, the unit continues to serve along India’s Himalayan border as part of the Special Frontier Force.

ENEMIES

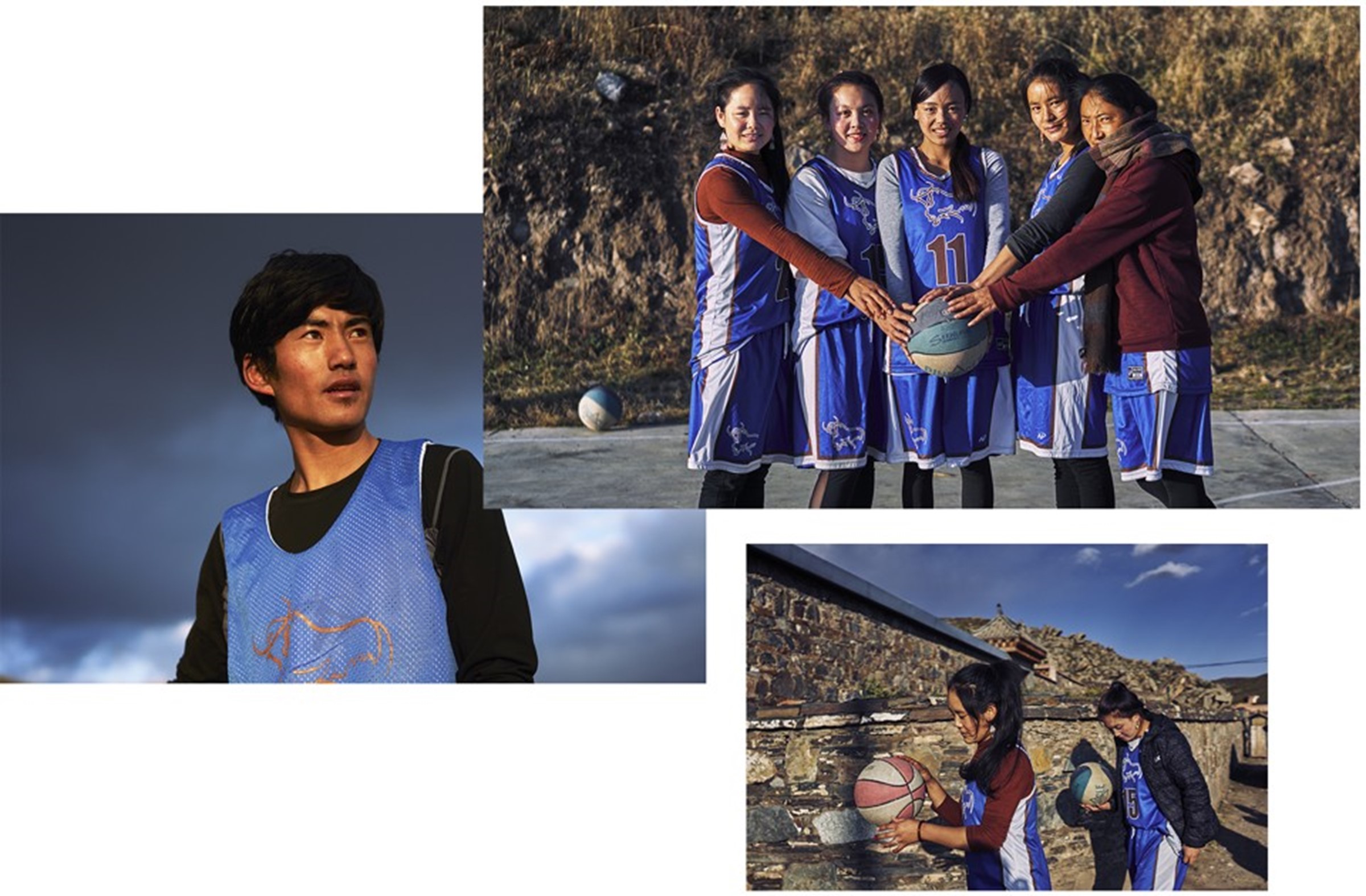

Many young Tibetan men joined the Indian military due to both the promise of exacting revenge on China and a lack of better career alternatives.

When Tunduk arrived in India, he was a 14-year-old orphan unable to communicate by means other than hand signals. “When we fled to India across the mountains we had problems with cold and food, and the Chinese were shooting at us,” he said. “And when we arrived, we had a big language problem.”

Once in India, Tunduk finished school and studied languages—he can now speak eight, he says, including English. Following graduation, however, Tunduk found that his status as a refugee afforded him few appealing career options. India conscripted many Tibetan refugees into road construction and repair teams for India’s Himalayan highways. That life didn’t appeal to Tunduk. And there was something else: he couldn’t shake his hatred for China.

“Army life was a very crazy life, but it was my best option,” he said. “I had no hope at that time to do anything else. No hope, and no aim. I faced a lot of problems, and I was affected by what happened to my parents. It made me angry. The truth is I joined the army to have revenge.”

“The army gave me a good life,” he added. “But I was always fighting for Tibet, not for India.”

Tunduk first saw combat in East Pakistan in 1971, and he fought in the 1986 battle on Siachen Glacier against Pakistani troops, in which 17 Tibetans died.

“Sometimes I became frustrated when I had to fight in other wars,” Tunduk said. “Our aim was to fight with China. Pakistan is not my enemy. China killed my parents and captured my country. China is my enemy.”

HOPE

Tunduk lives at an isolated collection of stone huts and seasonal tents called Man on the Indian shore of Pangong Lake, a thin 83-mile-long lake at an altitude of 13,940 feet, which forms part of the border between India and China in the Ladakhi Himalayas. Only nine families permanently inhabit Man, and Tunduk is the only Tibetan among them.

The lake, which is about three miles across at its widest point, is the highest saltwater lake in the world. It is the epitome of a Tibetan landscape. “After 27 years in the army, I came here because it reminds me of Tibet,” Tunduk said.

It is a long, difficult journey to Pangong Lake from the Ladhaki capital of Leh. The road is sometimes almost indiscernible as it cuts across steep mountain faces and down arid, high-altitude valleys. This road, like many in Ladakh, was constructed and maintained by Tibetan refugees pressed into construction gangs by the Indian government in the 1960s. Even today, small troupes of Tibetan road workers, comprising both men and women, are constantly at work in some of the harshest conditions imaginable. They keep India’s Himalayan roads clear, removing large rocks deposited by landslides or filling in potholes. All by hand. They live in small encampments made from old parachutes, located on what little flat ground there is. There are no trees for shade, and there is no water except for a trickle of snowmelt. Living their lives above 15,000 feet, they endure a lonely and miserable existence.

The road to Pangong Lake crosses the Chang La pass, which tops out at 17,688 feet, roughly the same height as Mt. Everest base camp in Nepal. There is an Indian army camp here, where soldiers deployed to the Himalayan border with China are sent to acclimate to the altitude. Past Chang La there are a few scattered settlements, but the Indian army constitutes most of the human footprint in this part of the Himalayas, underscoring lingering tensions with China about territorial rights in this barren, rugged territory, which date back to the 1962 Sino-Indian War.

After hours of weaving up and down mountain passes and endless switchbacks, the road enters a long valley and rounds the base of a mountain, where the ridgelines ahead seem to peel apart like curtains, revealing Pangong Lake.

The road to Pangong Lake from the Ladhaki capital of Leh. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

The lake is complete, abandoned isolation. The water is a collage of deep blue and aquamarine, contrasting sharply with the earthen oranges, browns, and reds of the surrounding mountains. All the colors, made more brilliant and crisp by the thin air, seem to swirl together; it’s like looking at a Monet painting up close. Distances seem to disappear across the massive landscape due to the increased definition of light at high altitude.

The sun’s radiation is pulsing and hot, but noticed only when the nearly constant wind settles for a brief and rare moment. The only hints of humanity are several small settlements of seasonal tents and primitive homes on the Indian lakeshore.

Tunduk is short but well-built. He stands straight and moves purposefully. His body and features have been hardened by a difficult life, not broken by it. He smiles constantly and speaks excitedly in English. He uses his hands a lot as he talks, placing a hand over his heart to show sincerity and a hand on your shoulder or knee when he addresses you.

His clothes are worn and sullied by the hard years of sustaining life in this inhospitable place. Around his neck he wears a necklace with an amulet given to him by the Dalai Lama. He handles the intricately woven design like a priceless work of art. “The Dalai Lama is my God and my king,” he said.

Tunduk used to graze cows, but the extended periods spent in the harsh climate around Pangong Lake became too demanding as he grew older. In the winter, when the temperatures sometimes drop to -40 Celsius, his cheeks and the tip of his nose would turn black from frostbite, he said. Now Tunduk sticks with growing barley and black peas—the same crops that his parents grew in Tibet when he was a boy.

“It’s a very hard life here,” he said. “We live like nomads, as my parents did.”

He stockpiles food, fuel, and other supplies for the winter in case snow closes the roads and he is cut off. The roof of his home is covered with firewood and dried saucers of yak and cow dung. The walls inside are lined with bags of rice and other foodstuff. And above the dinner table is a shrine to the Dalai Lama.

Only about two miles of water separate Tunduk’s home from Tibet. Tantalizingly close, but Tunduk has not set foot in his homeland since 1959. And as he grows older he admits the chances of him ever returning home are fading. Yet he has not given up hope.

“I’m still waiting for freedom,” he said. “And when Tibet is free one day, I will walk back home from here. I will try my best.”

Different Techniques

Tunduk married his wife, Ganyen Tsultime, on Dec. 10, 1989—the same day the Dalai Lama received the Nobel Peace Prize. “We met too late to have children,” Tunduk said. His younger sister, Khunda now lives in Simla, India, and has a daughter who is a nurse in California.

Tsering Tunduk outside his home on the Indian side of Pangong Lake. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

Tunduk and his wife spend nights in the sanctuary of their home. They sleep, eat, and pass time in the main room, which is heated by a stove that burns a combination of wood and yak dung. As the roof timbers creak in the Himalayan wind, Tunduk plays cards with a neighbor. There is a TV, and it is tuned to Indian news. Despite his isolation, Tunduk uses television to stay apprised of what’s happening in the world, and he is well versed in foreign affairs. He compares the current plight of Syrian refugees with that of Tibetans.

“I see a lot of countries with problems today; Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Ukraine,” he said. “I see these things, and I know what these people are going through. We had our dark times, too. Where there is a war, there is a sad story. Orphans and casualties—it’s always the same.”

Tunduk, who is devoutly Buddhist, believes that he is a sinner because of what he did as a soldier. He killed in combat and is deeply ashamed of it. To atone for the sins he believes he has committed, Tunduk has resolved to live life according to the teachings of the Dalai Lama.

“My medicine is to be kind, to make others happy,” Tunduk said as he sat outside his home, sipping on butter tea on a cloudless morning. The sun was bright and strong and still low over the Tibetan mountains on the opposite side of the lake.

“We are all the same in our hearts,” he went on, looking toward Tibet. “We want to be happy and to not suffer. We all believe in the same God (In my analysis, no Tibetan Buddhist expresses his religious belief using the term God); we just have different techniques.”

NOLAN PETERSON

Nolan Peterson, a former special operations pilot and a combat veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan, is The Daily Signal’s foreign correspondent based in Ukraine.

Related

Tibet: The Forgotten Refugee Crisis